Parkinson’s Disease and the Gut (Part 1)

by Melita Petrossian

In Part 1 of this 3-part blog I cover questions or concerns that many of my patients with Parkinson’s disease (PD) have that center around the gut.

- Constipation/delayed gastric emptying

- Dietary recommendations for PD in general

- Protein interactions with levodopa

- Dietary interactions with MAO-B inhibitors

- Connection of PD and the gut

- Antibiotic impact on gut bacteria

- The outlook for prevention or prevention progression for PD

1. Gastrointestinal symptoms of Parkinson’s disease

Up to 70% of patients with PD have gastrointestinal symptoms, often beginning years prior to the onset of motor symptoms, along the entire length of the gastrointestinal tract. I will describe the issues that can arise from top to bottom, so to speak.

Symptoms of the mouth and throat include the slowing down and reduction of the swallow response, resulting in drooling or repeated swallows being required in early stages of PD. As the disease progresses, swallowing difficulty (known as dysphagia) may worsen, resulting in aspiration (going down the wrong pipe), which can be silent (not noticed) or associated with coughing, choking, or pneumonia. Dysphagia and aspiration should be evaluated by a swallow study, performed by a speech therapist. Treatment recommendations include chewing more slowly, clearing one’s throat before taking another bite, eating while sitting up with the chin tucked, and changing the texture of the solids and liquids to be easier and safer to swallow.

The swallow response is a subconscious movement of the muscles of the mouth and pharynx and PD affects these subconscious movements. In the same way that the blink reflex reduces, the swallowing becomes less frequent. This results in drooling (known as sialorrhea) because the saliva is not being swallowed as frequently. Drooling can be treated with botulinum toxin (e.g., Botox) injections into the salivary glands to reduce saliva production.

Symptoms related to the stomach include bloating, indigestion, and early satiety, which typically reflect delayed stomach (gastric) emptying, sometimes known as gastroparesis. The gut movements (known as peristalsis) are coordinated by nerve cells surrounding the length of the gastrointestinal tract, and therefore may slow down or become uncoordinated the same way that movements of the limbs can be slowed or uncoordinated. This may be due to loss of enteric (gut-related) dopamine cells and degeneration of vagal nuclei (the nerve cells in the major nerve that controls the gut, the vagus nerve). A major issue of delayed gastric emptying is delayed action of levodopa (e.g., Sinemet or Rytary) because the medications move more slowly through the stomach and into the small intestine, where they are absorbed. This delay may be minimized by taking the medication on an empty stomach. Treatment of gastroparesis includes dietary modification (blenderized food) and monitoring of nutritional status. If the delayed gastric emptying is severe, there are medications that can help, such as domperidone and erythromycin. Please note that metoclopramide (Reglan) and prochlorperazine (Compazine), medications used for gastroparesis caused by diabetes, should not be taken by Parkinson’s patients because they block dopamine and may make motor symptoms worse.

Symptoms related to the lower gut. A very common symptom of parkinsonism, which can be present years prior to onset of motor symptoms, is slow-transit constipation. The term slow-transit refers to constipation that is due to the gut slowing down as waste products move through. This is similarly due to slowed peristalsis as in the case of delayed gastric emptying. Sedentary lifestyles, lack of adequate hydration, and the Western diet (low fiber) exacerbate constipation.

Chronic constipation is a major issue on many levels, but one of the main concerns from the day-to-day perspective is that constipation can worsen gastroparesis, thereby delaying the action of levodopa effect further. In addition, chronic constipation is associated with hemorrhoids, anal fissures (tears – ouch!), diverticulosis (weakening of colon wall which can cause bleeding and infections), and even up to a two-fold increased risk of colon cancer when severe. Intermittent treatment of constipation (getting “stopped up” for several days, taking laxatives, then having multiple bowel movements each getting looser and looser) results in alternating constipation plus diarrhea, dubbed “constirrhea” by one of my patients. Therefore, it is best to stay on top of the bowel movements and use non-medication and medication options to stay regular, with a bowel movement every day or two.

For more on management of constipation, please see Part 2 of this blog.

2. Dietary recommendations for patients with PD

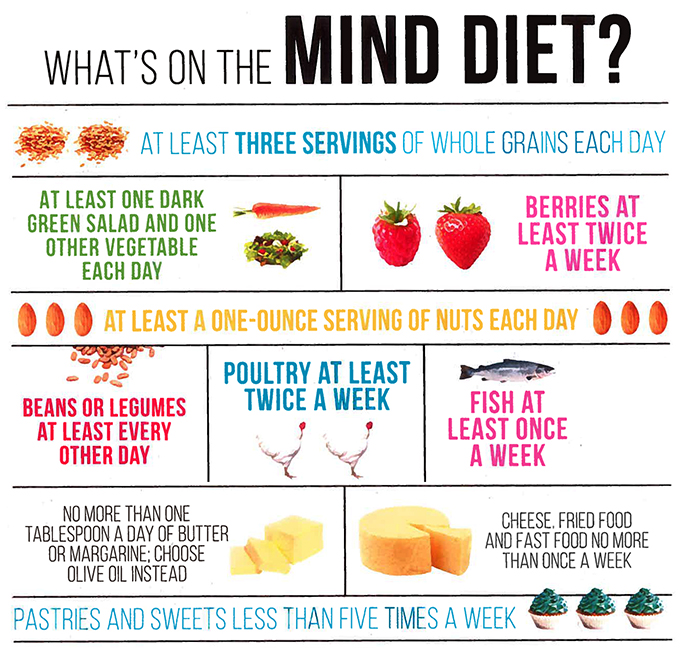

There are no specific diets that have been shown to reduce progression of PD. However, there is good reason to believe that a well-balanced, nutritious diet (one that might be recommended for any person in the age range) would be best. Patients with coronary artery disease, kidney disease, and diabetes should consult their medical doctors and nutritionists as those conditions have other dietary restrictions or priorities. In those without other medical conditions, one might extrapolate from success in preventing Alzheimer’s disease with the use of the Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurogenerative Delay (MIND) diet that there may be benefit in Parkinson’s as well since both are neurodegenerative diseases and involve cell dysfunction due to build-up of toxic proteins.

The MIND diet has 15 dietary components, including 10 “brain-healthy food groups”:

- Green leafy vegetables

- Other vegetables

- Nuts* (may recommend crushed or nut butters)

- Berries (especially blueberries and strawberries)

- Beans

- Whole grains

- Fish*

- Poultry

- Olive oil

- Red wine* — with caution – see below

The five unhealthy groups are:

- Red meats

- Butter and stick margarine

- Cheese

- Pastries and sweets

- Fried or fast food

The MIND diet includes at least three servings of whole grains, a salad and one other vegetable every day. It also involves snacking most days on nuts and eating beans every other day or so, poultry and berries at least twice a week and fish at least once a week. The MIND diet recommends limited eating of the designated unhealthy foods, especially butter (less than 1 tablespoon a day), cheese, and fried or fast food (less than a serving a week for any of the three).

However, because this diet has not been studied in PD, where patients may have balance issues which could worsen with alcohol, I DO NOT recommend a daily glass of wine. The supplement resveratrol may be taken instead. I also do not recommend as strict a limitation of cheese and butter, but I do recommend limiting excess sugars and processed foods. It seems to me that it would be more optimal for a patient to enjoy high-quality food of limited quantity, even (on occasion) rich foods or pastries, rather than having high quantities of low-quality, processed foods such as “diet” versions of food, which typically have higher sugar content when advertised as “fat-free” or may use more chemicals to substitute for flavor. For example, dark chocolate is known to have anti-oxidant qualities so it would seem that a small amount (an ounce for example) of good quality chocolate, enjoyed with thoughtfulness, would do better than abstaining altogether or attempting to abstain and then “breaking a diet” with binges of low-quality chocolate.

Regarding fish intake, I would recommend avoiding high-mercury fish:

- King Mackerel

- Marlin

- Orange Roughy

- Shark

- Swordfish

- Tilefish

- Ahi Tuna (albacore tuna has lower mercury content and can be had once a week).

Mercury content information is located at the EPA website.

Patients with Parkinson’s may have swallowing difficulties and dietary recommendations may vary depending on the severity of the condition. In general, high-risk foods to avoid in the context of swallowing include whole nuts, popcorn, hard candy, and tough meats. Some patients may be advised to maintain a dysphagia diet, which may recommend pureed foods or mechanical soft foods (e.g., meatloaf), and may recommend liquids to be thickened to the consistency of nectar or honey. These diets are recommended in conjunction with a swallow evaluation by a speech/language pathologist (SLP, i.e., speech therapist). If a PD patient has coughing/choking with food, liquid or meds, even if only on occasion, it’s important to notify the medical team to evaluate further.

3. Protein interactions with levodopa

For patients who are taking levodopa (carbidopa-levodopa in the forms of Sinemet, Rytary, or Parcopa; or benserazide-levodopa, known as Madopar), protein in the gut inhibits absorption of levodopa. That is, taking the medication with or just after a meal makes the medication less effective, or delays the onset of action, or even may cause the medication not to kick in at all. For this reason, levodopa should be taken on an empty stomach. I recommend taking the medication AT LEAST 30 minutes prior to a meal, or AT LEAST 60 minutes after finishing a meal. This does not mean a meal has to be taken at that half-hour mark, just that there should be a delay prior to eating. Also if patients are taking medications 4 or 5 times per day, they may still eat only 3 meals, meaning that each dose does not have to be followed by a meal. The medications should be taken as consistently as possible at the same times per day but on occasion adjustments may be made if there is a late meal.

Please note that the only food that interferes with absorption of levodopa is protein (which is found in meat products, dairy products, beans, legumes and nuts, among other types of foods). Therefore, if a patient wants to have a small snack just before a dose of levodopa, there is no issue if the snack is protein-free (such as coffee and toast in the morning, berries and vegetables, etc.).

The total protein intake should be of moderate level – protein is still important for general health and maintenance of muscle. On average this is about 50-60 grams per day, or 2-3 servings of protein-rich food per day. Again, patients with kidney disease need to confer with their nephrologists about the optimal daily dose of protein. For patients with PD who do not have other protein-intake related considerations, the daily dose does not have to be limited, just the timing adjusted to reduce interference with levodopa intake. Patients with PD who are not taking levodopa do not need to be concerned about protein intake and meal timing.

4. Dietary adjustments with MAO-B inhibitors

The medications rasagiline (Azilect), selegiline (Eldepryl, Emsam, Zelapar), and the new medication safinamide (Xadago) are MAO-B inhibitors. This means they reduce the metabolism of the brain’s natural dopamine, thereby causing more dopamine to be available for use.

The labeling on the medication advises patients to follow a low-tyramine diet. However, this dietary recommendation on the labeling is because MAO-B inhibitors are in the class of MAO inhibitors in general. Non-selective MAO inhibitors would also reduce the metabolism of the amino acid tyramine, which can cause elevated levels of tyramine, which would manifest with high blood pressure and other cardiovascular side effects.

When taken at the appropriate dose, there is no dietary restriction that is actually required. The doses that are FDA-approved for these 3 selective MAO-B inhibitors are shown to be specific for MAO-B, and therefore I do NOT limit metabolism of tyramine. Patients should NOT take doses higher than recommended (1 mg for rasagiline, 10 mg for selegiline). Tyramine is found in aged cheeses, sourdough bread, soy-based products, draft beer, red wine, fermented cabbage (such as sauerkraut and kimchi) and in cured meats. Of course, patients should not be taking an excess of tyramine-rich foods but when eaten in moderation, there is virtually no risk of the tyramine crisis.

5. Connection of PD and the gut

PD patients and normal control subjects have different types of gut bacteria, known as the gut microbiome. In addition, abnormal protein deposits of alpha-synuclein seen in the brains of patients with PD have also been found in the gut prior to development of motor symptoms, up to 20 years prior to diagnosis. There are a number of theories and studies that look into the connection that the gut may have with relation to the onset of Parkinson’s disease. A detailed summary of research studies of the brain-gut connection in our understanding of Parkinson’s disease can be found in Part 3 of this 3-part blog series.

6. Antibiotic impact on gut bacteria

Because antibiotic use is one of the main factors in changing natural gut bacterial profiles, I would also remind patients to exercise caution about antibiotics – both in their diet and in their own health care. There is a movement to limit the amount of antibiotics in meats and dairy products, and one should make efforts to seek out antibiotic-free products for home cooking and when eating in restaurants. Antibiotics should also be limited to use in conditions clearly caused by bacterial infection. Too often antibiotics are given for viral infections such as the cold or the flu, in some cases at the insistence of patients themselves. Overuse of antibiotics in both situations can result in antibiotic-resistant bacteria as well as the previously mentioned changes in gut flora. The limitation of unnecessary antibiotics is important for all people, not just those who have PD, in order to limit the rise of antibiotic-resistant superbugs.

7. The outlook for prevention or prevention of progression for Parkinson’s disease

There is a lot of promising ongoing research to identify biomarkers for PD utilizing gut tissues such as saliva. In the future, these may serve to identify people at risk of developing PD, and/or help determine markers of progression for patients with PD. Many earlier stage patients may be assessed for risk and more timely assessments of disease could be made. Drug development could potentially target very early stage disease versus treating clinical progression.

In the meantime, there is no evidence to support the use of probiotics or pre-biotics to supplement the gut microbiome – yet. This is an area of early research for the management of gut-related symptoms such as constipation. The hopes of preventing disease progression may take larger and longer studies.

At this point, based on current evidence, I would encourage healthy eating as detailed above.

About the Author

Melita Petrossian

Melita Petrossian, MD, is Director of Pacific Movement Disorders Center and is a fellowship-trained neurologist with clinical interests and expertise in movement disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, essential tremor, dystonia, gait disorders, ataxia, myoclonus, blepharospasm, hemifacial spasm, Meige syndrome, spasticity, tics, and Tourette’s syndrome. She also specializes in Parkinson’s-related conditions such as Dementia with Lewy Bodies, progressive supranuclear palsy, multiple system atrophy, corticobasal degeneration, primary freezing of gait, and Parkinson’s disease dementia.

Last updated: December 17th, 2021