Ventriculoatrial Shunt Hydrocephalus Treatment

Who needs a ventriculoatrial shunt?

Patients who need a ventriculoperitoneal shunt (VP Shunt) but have scarring or infections in their abdomen may benefit from placing the drainage catheter directly into the bloodstream.

Additionally, patients who already have VP shunts but need further drainage to achieve symptom relief may need to drain directly into the lower pressure venous vessels. This is achieved with a ventriculoatrial shunt (VA Shunt).

This procedure is also well tolerated and carries similar risks to a VP shunt. Though the risk to the abdominal organs is eliminated, there is a slightly higher risk of bloodstream infections or heart valve infection (endocarditis). Also, there is a higher risk in patients with cardiac arrhythmias as the catheter can irritate the heart rhythm control region.

Placing a new VA shunt requires an inpatient stay. However, converting from a VP to VA shunt can be done on an outpatient basis for some patients.

What are the risks of ventriculoatrial shunt?

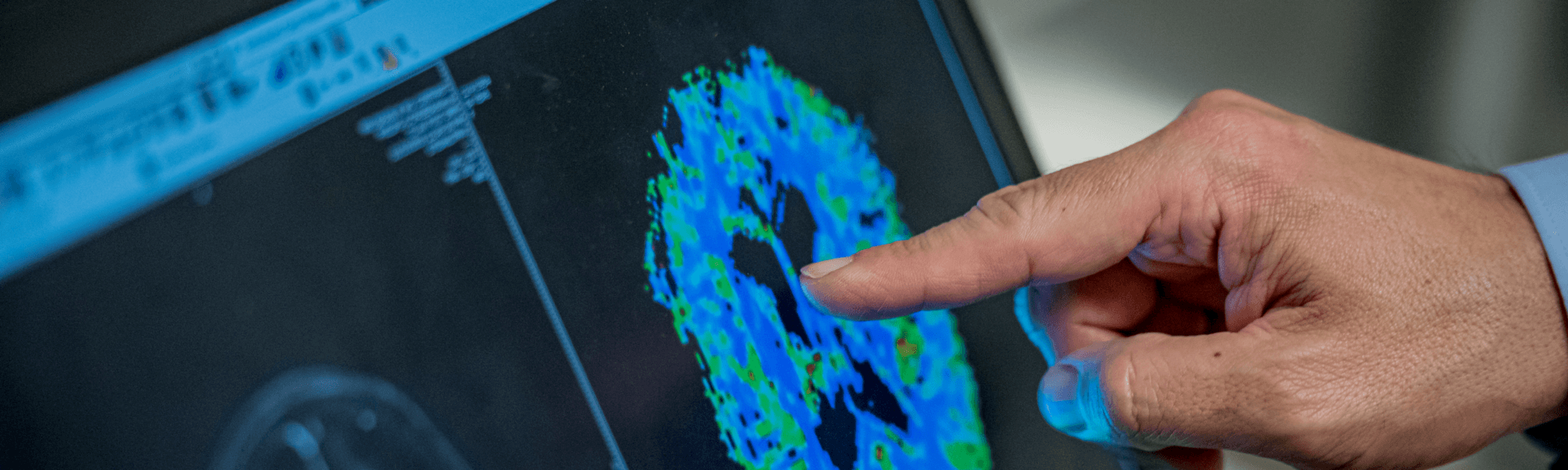

A ventriculoatrial shunt is used to treat hydrocephalus by diverting excess cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from the brain to the heart. However, like any surgical procedure, it carries certain risks and potential complications.

Common risks of a ventriculoatrial shunt include:

- Infection: Bacteria can infect the shunt, leading to fever, headaches, or redness around the surgical site. This requires immediate medical attention and possibly shunt removal.

- Shunt Malfunction: The shunt can become blocked or fail, preventing proper drainage of CSF. Symptoms like headaches, nausea, or vision changes may indicate shunt malfunction.

- Blood Clots: As the shunt drains fluid into the heart, there is a risk of blood clots forming in the veins. This can lead to complications like deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism.

- Over- or Under-Drainage: The shunt valve may allow too much or too little fluid to drain, causing symptoms such as headaches, dizziness, or swelling at the shunt site.

- Heart Complications: Rarely, the shunt may cause arrhythmias or other cardiac issues due to its placement in the heart.

What are the 2 types of shunts?

There are two main types of shunts used to treat hydrocephalus: ventriculoperitoneal and ventriculoatrial shunts. Each serves the purpose of diverting excess cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from the brain to a different part of the body for absorption.

Ventriculoperitoneal Shunt:

- This is the most common type of shunt. It drains CSF from the brain’s ventricles to the peritoneal cavity in the abdomen, where the fluid is absorbed by the body.

- The shunt consists of a catheter, valve, and distal tube. The valve regulates the flow, preventing over-drainage.

- It is preferred due to its lower risk of complications and infections. However, it may still cause issues like shunt malfunction or abdominal complications.

Ventriculoatrial Shunt:

- This shunt diverts CSF from the brain’s ventricles to the right atrium of the heart. It is used when abdominal complications or previous shunt failures make ventriculoperitoneal shunting unsuitable.

- Although effective, it carries higher risks, including infection and blood clots in the heart.

- Regular monitoring is crucial to ensure the shunt functions properly and to manage potential complications.

Choosing between these shunts depends on individual patient factors and the underlying cause of hydrocephalus.