PATIENT STORY: One Person, One Cancer

by Zara Jethani

Precision medicine tailors treatment to the patient’s unique biological makeup

WRITTEN BY TRAVIS MARSHALL

PHOTOGRAPHED BY JULIE CAMPBELL

When Nicole Saldivar was diagnosed with the brain tumor glioblastoma at age 16, her parents Alfredo and Kathia Saldivar took her to a pediatric cancer center where her doctors followed the standard protocols for her treatment. But chemotherapy and radiation did nothing to stop the tumor’s rapid growth.

Nicole soon lost the ability to speak and walk as the tumor grew, and her doctors said they were out of options. Her parents took her to cancer centers throughout Los Angeles, desperately searching for a miracle cure that could save their daughter’s life. But the answer was always the same: There’s nothing we can do.

Then one day in October 2015, a copy of the Saint John’s Cancer Institute’s Innovations magazine showed up in the Saldivars’ mailbox with a profile inside of Pacific Neuroscience Institute‘s Santosh Kesari, MD, PhD, director of neuro-oncology at Providence Saint John’s Health Center and chair of Saint John’s Cancer Institute’s department of translational neurosciences and neurotherapeutics. Nicole’s father made an appointment the same day, and Dr. Kesari did something none of her other doctors the family had seen across Los Angeles did: He analyzed the genetic profile of her tumor. “She had a mutation of the PI3K gene, one of the oncogenes for glioblastoma,” Dr. Kesari says. “We knew that a medication called everolimus is approved for this mutation in breast cancer and renal cancer, so we believed it could work for her glioblastoma.”

This outside-the-box thinking paid off. Within two months of starting treatment with everolimus, Nicole’s tumor had shrunk by 50%, and a year later it was 93% gone. She’s currently undergoing occupational and speech therapy to regain her speech and motor functions. “I can’t wait to ride a bike and run again,” she says.

THE NEW PARADIGM IN CANCER CARE

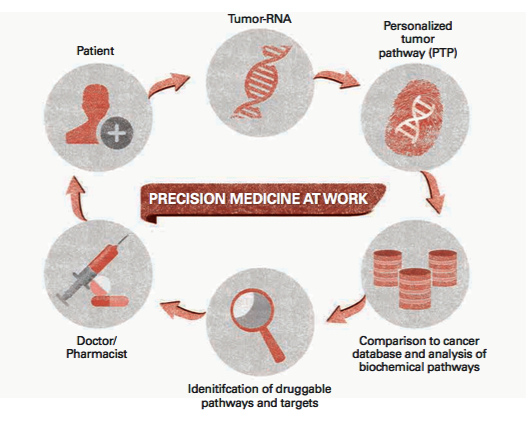

Nicole’s experience is a textbook example of a new paradigm in cancer care called precision medicine, in which physicians use genetic testing to identify mutations in individual patients’ cancers and treat them with therapies targeted to those mutations rather than following standard protocols for broad therapies based on cancer type.

“Nicole’s case shows what precision medicine can do,” Dr. Kesari says. “If we can understand the critical drivers in the mutations of each patient’s tumor and then identify drugs that target them, we have the potential to really transform the survival of these patients.”

Precision medicine is still an emerging field, but it has grown rapidly in recent years. It’s paving the way for more successful treatments of some of the most challenging cancers. “Personalized medicine is about looking at the individual patient’s tumor to find out how that tumor is vulnerable,” explains Steven J. O’Day, MD, director of immune-oncology and clinical research at the Institute, who is collaborating with Dr. Kesari on several precision medicine trials for a variety of tumor types. Dr. O’Day has had notable success applying targeted immunotherapies and molecular therapies to the treatment of melanoma. “Melanoma, historically, was one of the worst-prognosis cancers,” he says. “Now in the span of five years it has become one of most treatable types of cancer because we found a key mutation that we can block, and we found ways to activate the immune system against the cancer.”

“Glioblastoma is where melanoma was 10 years ago,” Dr. O’Day adds. “It’s resistant to chemo, the patients are young, and they often die quickly. We need to find those vulnerable mutations and molecular targets. Dr. Kesari and I are collaborating to figure out ways to do that, and melanoma is the model. What Dr. Kesari does is really scrutinize the cancers to see if they have mutations found in other diseases that are vulnerable to targeted therapies.”

PRECISION MEDICINE REQUIRES INDUSTRY-WIDE COLLABORATION

Precision medicine is the way of the future for oncology. But today’s doctors have only a fraction of the information they need, which is why most patients’ tumors aren’t genetically profiled—at least not during the first line of treatment. “If a disease has mutations that have been shown to have therapies that help that patient, then we’ll profile the tumor at baseline. But we must be careful about not overemphasizing mutations that may not be relevant,” Dr. O’Day says. “Even if they are relevant, we may not have a treatment yet. But in the coming years, I think we will profile more and more tumors. We’ll know what the vulnerabilities are. That’s why there’s a huge push for widespread, collaborative efforts on a national and international scale to build a database of all vulnerable mutations, cross-referenced with any targeted therapies known to be effective. “All the human genes have been mapped in the Human Genome Project, so now it’s a matter of doing the same thing for these cancer driver mutations,” Dr. O’Day says.

President Obama took a big step in that direction when he announced the Precision Medicine Initiative in his 2015 State of the Union Address. The initiative allocated $215 billion to biomedical research through the National Institutes of Health and other agencies, including the Beau Biden Cancer Moonshot Initiative led by Vice President Joe Biden, whose son Joseph “Beau” Biden III died from brain cancer like Nicole’s.

“It’s going to take a huge effort to pinpoint all the critical mutations,” Dr. Kesari says. “We also don’t have drugs for all the mutations, so we need to keep developing new drugs as well.”

PNI AND JOHN WAYNE CANCER INSTITUTE AT THE FOREFRONT OF PRECISION MEDICINE

Over the last 25 years, the Institute has been one of the pioneering cancer centers that helped make precision medicine part of the national conversation. “We’ve been working on precision medicine since the early 1990s, and now everybody is starting to do it,” says Dave S. Hoon, PhD, director of the translational molecular medicine department.

Dr. Hoon’s lab has been instrumental in developing molecular/diagnostic blood and tissue assays to detect minimal residual disease as well as the process known as liquid biopsy (also called blood biopsy and urine biopsy), which will dramatically change how oncologists diagnose, monitor and treat certain patients—especially those with tumors that are hard or impossible to biopsy surgically. Liquid biopsy involves collecting and analyzing tumor cells, DNA, micro RNA and other biomarkers that tumors shed into the blood and urine rather than requiring a solid tissue biopsy from the tumor itself. Dr. Hoon is currently studying the use of blood biopsies for melanoma, prostate cancer and glioblastoma, and urine biopsies for prostate, urological and lung cancers.

“This allows us to do real-time tests without constantly biopsying the tumor. We can identify mutations that are potentially targetable by certain therapies, but we can also use them as biomarkers for detection and prognosis,” Dr. Hoon says. “This benefits early diagnosis and progression, so we can evaluate and treat it earlier. We can also tell if patients are responding to treatment, and we can quickly switch treatment if the findings suggest there is no response. That will spare people from the side effects of therapies that don’t work and prolong survival. That’s the end game.”

In other words, not only can these biomarkers be used to genetically profile a patient’s cancer from a simple blood or urine sample, but doctors can take samples daily or weekly to create a comprehensive data set that allows them to watch the cancer’s progress over time and know right away if a treatment isn’t working or how the cancer is growing or evolving.

“Liquid biopsy used to be on the fringe. Now it has the attention of the oncology world,” Dr. O’Day says. “The ability to diagnose cancer as well as monitor response to the treatment and to immediately stop or switch therapies if the tumor starts to develop resistance will be a huge part of precision medicine.”

The Saldivars feel incredibly lucky they found Dr. Kesari and that they didn’t give up hope when other doctors said there was nothing left to do. Because research on targeted therapies for glioma is in an early phase, there was no guarantee that profiling Nicole’s brain tumor would lead to the discovery of a treatable mutation—or even that everolimus would have any effect on the mutation.

“She was part of an N-of-1 study,” meaning a single-patient study, Dr. Kesari says. “We need to study this in a much broader way so more patients can benefit.”

To find out more about our Precision Medicine Programs, please contact Dr. Kesari’s clinic at 310-829-8265. For more information on supporting precision medicine, please contact Mary Byrnes in the Office of Development at 310-582-7102.

Adapted from the original article in INNOVATIONS, SPRING 2017 published by Saint John’s Cancer Institute at Providence Saint John’s Health Center.

About the Author

Zara Jethani

Zara is the marketing director at Pacific Neuroscience Institute. Her background is in molecular genetics research and healthcare marketing. In addition, she is a graphic designer with more than 20 years experience in the healthcare, education and entertainment industries.

Last updated: August 2nd, 2017